If you are writing React, you definitely are no stranger to setState and useState . These are the two primary ways to update the state in your application. This post aims to unpack all the quirky behaviours around these two APIs. If you are a seasoned React developer, you probably know all of them by now. That said, it is still worth revisiting them since there are lots of subtle nuances about them and they can definitely bite you if you are not careful.

We are going to take a look at a very simple counter. Out of the box, it doesn’t have a lot going on.

class Counter extends Component {

state = { count: 0 }

increment = () => {

this.setState({ count: this.state.count + 1 })

}

decrement = () => {

this.setState({ count: this.state.count - 1 })

}

reset = () => {

this.setState({ count: 0 })

}

render() {

return (

<main className="Counter">

<p className="count">{this.state.count}</p>

<section className="controls">

<button onClick={this.increment}>Increment</button>

<button onClick={this.decrement}>Decrement</button>

<button onClick={this.reset}>Reset</button>

</section>

</main>

)

}

}

render(<Counter />, document.getElementById("root"))useState

First let’s take an uncomfortably close look at the useState API. The first well-known quirk about useState is that it is asynchronous. It can certainly be a recipe for headaches.

let’s say we refactored increment() as follows:

increment = () => {

this.setState({ count: this.state.count + 1 })

this.setState({ count: this.state.count + 1 })

this.setState({ count: this.state.count + 1 })

console.log(this.state.count)

}Take a lucky guess about what the value that gets logged out would be and what value the count would be updated to?

If the initial count is 0, after we click on increment. The state will be 1 instead of 3, because React will batch the operations up, figuring out the result and efficiently make that change. Also it will log out 0 instead 1 since setState is async.

This is explained in the documentation of setState.

“setState() does not immediately mutate this.state but creates a pending state transition. Accessing this.state after calling this method can potentially return the existing value. There is no guarantee of synchronous operation of calls to setState and calls may be batched for performance gains.”

Now we refactored increment() again as follows:

increment = () => {

this.setState({ count: this.state.count + 1 })

this.setState({ count: this.state.count + 2 })

this.setState({ count: this.state.count + 3 })

console.log("this.state.count", this.state.count)

}What will the new value of the state be?

If the initial count is still 0, after we click on increment. The state will be 3 and it will still log out 0. This is due to another feature of setState: it does shallow merge to update state.

This means that the above operation is effectively as follows

Object.assign(

{},

yourFirstCallToSetState,

yourSecondCallToSetState,

yourThirdCallToSetState

)

// or

const newState = {

...yourFirstCallToSetState,

...yourSecondCallToSetState,

...yourThirdCallToSetState,

}When there’s duplicate keys, the last one wins.

So far we are calling setState with by passing in an object to the API to update the state. However, it turns out that setState also takes in a function as an argument.

This means that we can refactor increment() as follows.

this.setState(state => {

return { count: state.count + 1 }

})Or use destructuring to make it evening cleaner.

const increment = () => {

this.setState(({ count }) => {

return { count: count + 1 }

})

}Since we can only merge objects in JavaScript not functions, when we update the state multiple times in a row, they will can behave as expected i.e. the effect will stack up and the state would be updated all at once.

If we rewrite the previous increment into

increment = () => {

this.setState(({ count }) => ({ count: count + 1 }))

this.setState(({ count }) => ({ count: count + 1 }))

this.setState(({ count }) => ({ count: count + 1 }))

console.log("this.state.count", this.state.count)

}The state would be updated to 3 after we click the button, as opposed to 1 as we saw before.(However the logged out value would still be 0 since this syntax does not change the asynchronicity nature of the API)

When adopting this syntax, there are lots of potentially cool things we could do here. For example, we could add some logic to our component.

Let’s stay, we wanted to add in a maximum count as a prop.

increment = () => {

this.setState(state => {

const { count } = state

const { max, step } = this.props

if (count >= max) return // notice here I didn't return anything. This is the same as return {count: this.state.count}. If we return nothing, it will not update the state

return { count: count + step }

})

}But there is a catch. Now the function we passed into this.setState also replies on this.props . You can see that this is not going to be good for testing, since we have to mount the entire component and pass in props in order to test it. But turns out that we can actually have a second argument in there as well — the props

increment = () => {

this.setState(({ count }, { max, step }) => {

if (count >= max) return

return { count: count + step }

})

}This allows us to pull the function that got passed into setState out of the component. This makes it way easier to unit test without having to mount the entire component.

After extracting the function out, we get

const incrementHelper = ({ count }, props) => {

const { max, step } = props;

if (count >= max) return;

return { count: count + step };

};

class Counter extends Component {

state = getStateFromLocalStorage();

increment = () => {

this.setState(incrementHelper)}

One last piece about useState. Before we talked about that it is async. What if we actually want to access the updated state? In JavaScript, the way to access async data is normally through callback functions. And unsurprisingly, setState takes a second argument in addition to either the object or function. This function is called after the state change has happened.

Based on the example above, we can have

this.setState(increment, () => console.log(this.state))This time, when we click the button, we will see the updated state gets logged out.

This additional callback we have here allows us to perform some side effects that we wish to happen after the state is updated.

One use case would be that we can use LocalStorage to update the cached state every time setState is called

increment = () => {

this.setState(

({ count }, props) => {

const { max, step } = props

if (count >= max) return

return { count: count + step }

},

() => {

localStorage.setItem("counterState", JSON.stringify(this.state))

}

)

}It would be cool if we can extract the second function out and do something like this

increment() {

this.setState(increment, storeStateInLocalStorage);

}

However t doesn’t work. it’s a bummer that the callback function does not have a copy of the state. It does not get any arguments. We could wrap it into a function and then pass the state in, or we can put the function onto the class component itself. i.e. it is a method of the class. Either way, we will lose the testability that we have for the first function argument of setState

useState

Now it’s 2020, let’s use Hooks like everyone else is doing.

Get ready to delete lots of code.

const Counter = ({ max, step }) => {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0)

const increment = () => setCount(count + 1)

const decrement = () => setCount(count - 1)

const reset = () => setCount(0)

return (

<main className="Counter">

<p className="count">{count}</p>

<section className="controls">

<button onClick={increment}>Increment</button>

<button onClick={decrement}>Decrement</button>

<button onClick={reset}>Reset</button>

</section>

</main>

)

}What if we tripled up our increment again?

const increment = () => {

setCount(count + 1)

setCount(count + 1)

setCount(count + 1)

console.log("count", count)

}The result remains the same. ie. will only update once and log out the previous state.

It also turns out that useState can take function as its argument too

const increment = () => {

setCount(count => count + 1)

setCount(count => count + 1)

setCount(count => count + 1)

}As it is discussed previously, there is no way to merge functions in JavaScript, so syntax will make the state go up to 3 at once.

However it gets only the state in this case. There is no second argument with the props. That said, we have them in scope. The reason(at least one of the reasons) useState does not support callback functions like setState is because, we can use useEffect to trigger side effects based on state changes.

There is another important difference here. Earlier with setState, we ended up returning undefined if our count had hit the max. What if we did something similar here?

setCount(count => {

if (count >= max) return

return count + 1

})Well, the counter will explode after it hit the max. This is core to the difference between how useState and setState works.

With setState, we’re giving the component that object of values that it needs to update. With useState, we’ve got a dedicated function to change a particular piece of state.

The fix is easy though, we just need to return the state as it is

const increment = () => {

setCount(count => {

if (count >= max) return count

return count + step

})

}useEffect

As I have alluded before, we can use useEffect to implement some kind of side effect in our component outside of the changes to state and props triggering a new render.

One use case is implement localStorage in useEffect

useEffect(() => {

localStorage.setItem(key, JSON.stringify({ value }))

}, [value])So we can even make our own custom hooks to make it even more usable

Do not use this in production. It has lots of unhandled edge cases

const useLocalStorage = (initialState, key) => {

const getInitialValue = () => {

const storage = localStorage.getItem(key)

if (storage) return JSON.parse(storage).value

return initialState

}

const [value, setValue] = useState(getInitialValue())

useEffect(() => {

localStorage.setItem(key, JSON.stringify({ value }))

}, [value])

return [value, setValue]

}Back to Class-Based Component

After taking a look at setState and useState. I want to revisit the class base component to show you one fundamental difference between class-based components and function components that is often overlooked.

import React, { Component } from "react"

class Counter extends Component {

state = {

count: 0,

}

increment = () => {

this.setState(({ count }) => ({

count: count + 1,

}))

}

decrement = () => {

this.setState(({ count }) => ({

count: count - 1,

}))

}

componentDidUpdate() {

setTimeout(() => {

console.log(`count, ${this.state.count}`)

}, 3000)

}

reset = () => {

this.setState(() => ({

count: 0,

}))

}

render() {

const { count } = this.state

return (

<div className="Counter">

<p className="count">{count}</p>

<section className="controls">

<button onClick={this.increment}>Increment</button>

<button onClick={this.decrement}>Decrement</button>

<button onClick={this.reset}>Reset</button>

</section>

</div>

)

}

}

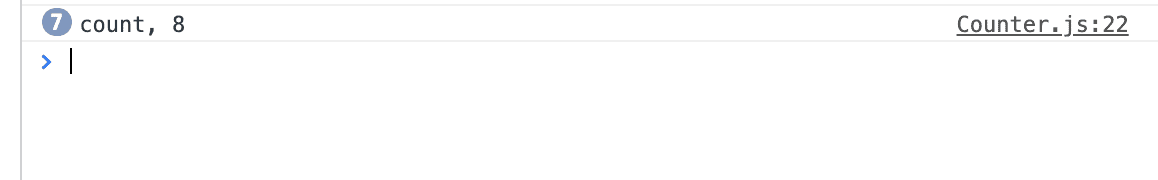

export default CounterThe delay in componentDidUpdate is intended to just create some space between the click and what we log to the console. If we click on the button a bunch of times we will see something like this

Why is that we are getting the same, updated state printed out to the console again and again?

Dan Abramov has an informative post on this exact topic as well How Are Function Components Different from Classes? — Overreacted

This is because, in the setTimeout function, we are referencing this.state.count, and React itself updates/mutates this over time so that we can read the fresh version in the render and lifecycle methods, which let us referencing the same this.state.value when all of those three second delay has caught up.

Now switch back to Hooks.

const Counter = ({ max, step }) => {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0)

const increment = () => {

setCount(c => {

if (c >= max) return c

return c + step

})

}

const decrement = () => setCount(count - 1)

const reset = () => setCount(0)

useEffect(() => {

setTimeout(() => {

console.log(`count: ${count}`)

}, 3000)

}, [count])

return (

<div className="Counter">

<p className="count">{count}</p>

<section className="controls">

<button onClick={increment}>Increment</button>

<button onClick={decrement}>Decrement</button>

<button onClick={reset}>Reset</button>

</section>

</div>

)

}

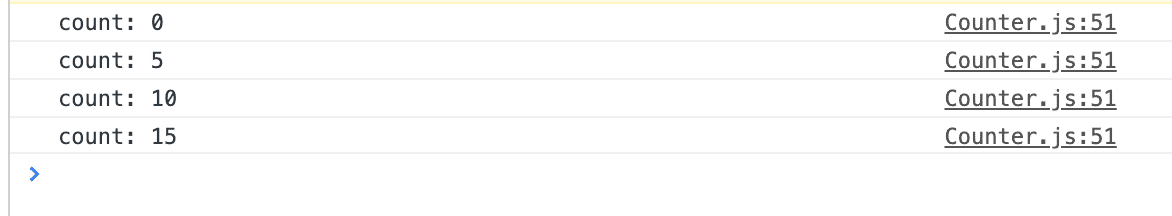

export default CounterThis time we have

This is not a fundamental difference to the ways that these two APIs(useEffect vs. componentDidUpdate) work. But a fundamental difference to the way JavaScript works.

In the case of a function component, it is a unique call of the function every single time and because of closure, the component is able to close over the correct props and state with which it was rendered and we are getting a copy of the state and props every single time, as opposed to referencing a class property on an object.